Reader. Dreamer. Writer.

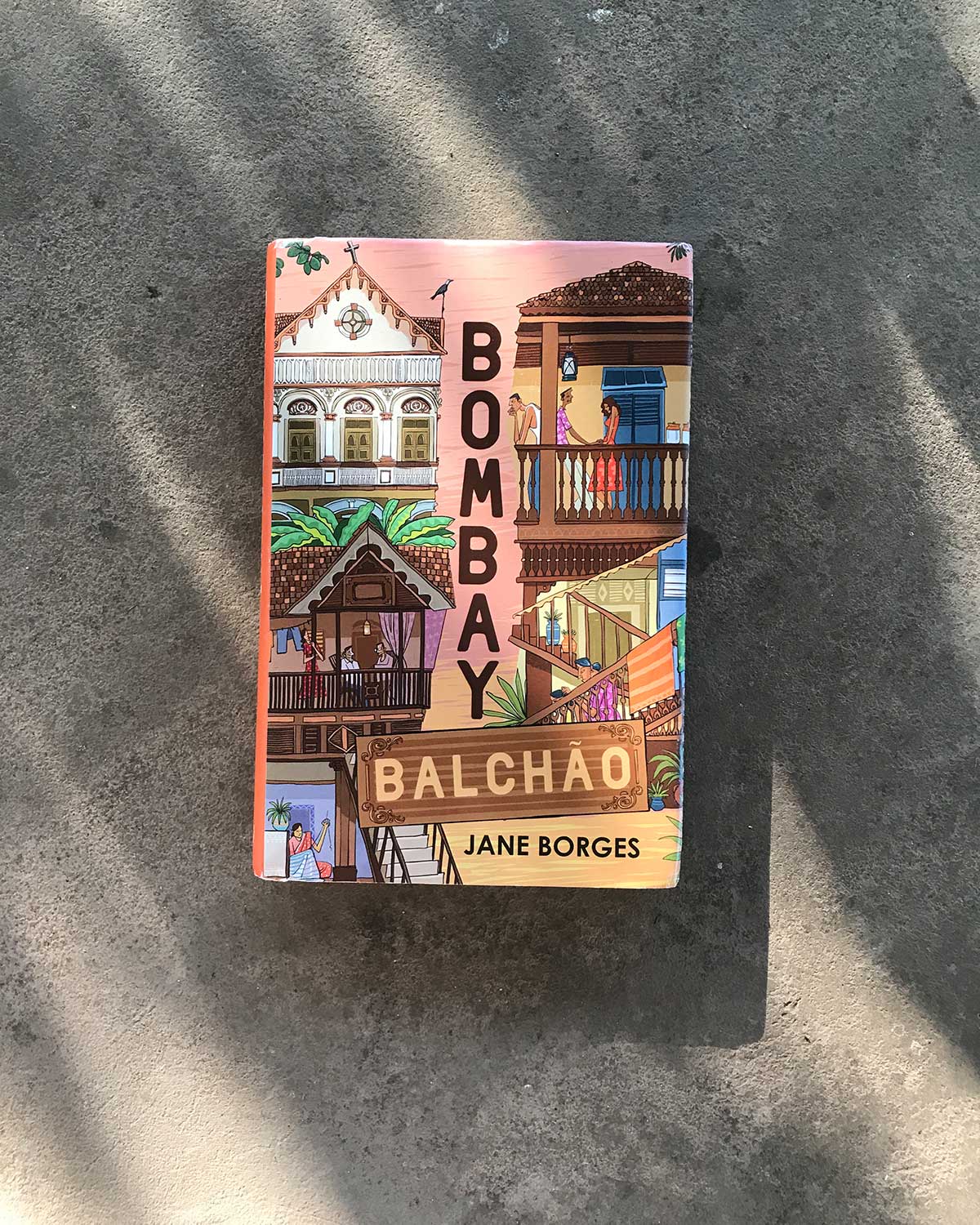

The first thing you notice about Bombay Balchão, the new Bombay novel (which I think should be a genre in itself), is the striking cover design by Mohit Suneja. The tightly packed buildings, with people milling around in the corridors, took me back to my pillion musings while stuck in Mumbai traffic, something no one warned me about when I moved to the city. Peering into dilapidated buildings with shared corridors and quaint balconies that stood on roadsides was a hobby and now, I was finally inside one.

Books set in apartments have a charm of their own because personal histories are shared—often tangled and mangled—and trivial episodes manifest as bigger events later on. Elif Shafak’s The Flea Palace, set in a decrepit Istanbul building is an example of eccentric apartment neighbours living a tragicomic life. Closer to home, Esther David’s Bombay Brides, about an Indo-Jewish housing society in Ahmedabad with matchmaking aunties, dream interpreters, Biblical kirtans sung in Marathi and dark-skinned brides, has a more histrionic flavour. In a similar vein, Bombay Balchão invites us into Bosco Mansion, a two-storeyed-six-flats-building in Pope’s Colony in Cavel, a Catholic neighbourhood in South Bombay.

At the heart of the novel are the Coutinhos, a Goan Catholic family. Among the elaborate cast are a widow who smuggles hooch to start a successful business, a recluse who finds solace in a lending library and becomes a crossword whiz, a single woman who learns to cook in her sixties, a flirtatious young lady who elopes on the day of her engagement swayed by the plots the future weddings of her kids, and many, many more people. Love (and lust)—sudden, withered, unrequited and reacquired—often cause havoc in the lives of the residents. There’s uproarious humour—the exorcism of Michael Coutinho over half-eaten chikkus made me shriek with laughter—Borges says it was the same for her while writing it. Even the funeral of the Coutinho son-in-law was more hilarious than mournful, in a way only life in Bombay can be.

Sandwiched between these comical developments are slivers of history that are a delight to bite into. Borges takes us through newer political and economic developments such as the Prohibition Act and Rent Control Act to disasters like the 1944 dockyard explosion to older, fascinating trivia like a bell with a crucifix adorning a temple as war loot, the bubonic plague in the 19th century, Tipu Sultan’s seize of estates of Mangalorean Catholics and the immigration from Portuguese-owned Goa.

With each chapter, I stumbled onto familiar locations and buildings which revealed their layers of antiquity. The Vasai suburbs, which are synonymous with cheap rented apartments, transformed into a battleground—the Maratha vs Portuguese ‘Battle of Bassein’. The Smoker’s Corner, a bookstore and lending library housing mostly popular fiction and comics, is a thriving, hidden gem. Irani bakery dates over keema pav and raspberry soda made me nostalgic about my own assignations there.

Borges’ Cavel, home to different communities, is a melting pot of culture, traditions and quirks. There are the native Christians (or East Indians, self-named to identify themselves with the East India company in the west-coast-Mumbai), Goan Catholics (laid-back, jolly, party loving types), Mangalorean Catholics (disregarded by Goans as shrewd and boring) and a few Hindus. The engagement party of Annette Coutinho felt like a scene straight out of the Pixar animated film Up, with Goan and East Indian women (bride’s side) flaunting floral dresses, skirts with printed blouses and bouffant hairstyles while the Mangalorean side (groom’s side) had women in heavy, embroidered sarees, and jasmine-wound hair in buns, (“like they’ve come for a funeral”, the Goans tsk-ed).

Milk Teeth by Amrita Mahale, another Bombay novel with a smaller cast which was released last year, explores housing and communal problems in 1990s Mumbai. Similar to Mahale’s Bombay, prejudices are commonplace in Cavel—friendship (and romance) between Pope’s colony and the poorer Cross Gully are forbidden, inter-community marriages are frowned upon and lack of fluent English is mocked—but grow weaker with time. Over the years, the neighbourhood evolves with its own traditions (baan dance, a version of ballroom dancing) and folklore.

Food—heirloom recipes, shared wine, birthday baath (coconut-semolina dish), Christmas gatherings with plum cakes and coffee—serves as a token of love. Forty-day fasts are traded for sorpotel and mutton xacuti in liberal households while rice gruel ‘pez’ with no meat (or sex) is followed in more conservative ones. Seafood is a staple—mackerel ‘bangda’ fry stuffed with recheado masala, prawn balchão pickles, pomfrets and Bombay duck are relished. Breakfasts are indulgent affairs with pao lathered with butter or marinated curries from the night before and the newer habits of takeaway dinners include Goan fish curries and vindaloos.

Borges’s debut novel (she co-wrote a non-fiction book in 2012) is as much an ode to contemporary Mumbai as to old Bombay. The nearly forgotten Cavel that she sets out to preserve on paper has the vinegary, tangy punch of the Goan-favourite balchão masala that the novel is named after. To the outsider, this is a book of wonder, richness and theatrical moments. To me, it brought alive the city I know and call home—landlord-tenant fracases, collapsing buildings, chaotic markets with loud bargaining, evenings marked by the cycle bell of paowallahs with “an assortment of breads, khaaris and nankhatais in tarpaulin bags” and the never-ending water problems. I want nothing more than to take a walking tour with Bombay Balchão as my guide. You will long for the same too.

This book review was first published on Huffpost India, which has now closed doors

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Two fantastic books about cultural nuances, food and buildings set in India