Reader. Dreamer. Writer.

A ghost who asks about a young wife’s sex life and curses her unapologetically; the formation of the first Bengali circus and story of the first Indian woman who performed with tigers; and desi pulp fiction. How thrilling! Here are three book recommendations, all translated from the Bengali by the prolific, Arunava Sinha, who has done more than 44 translations so far. Though unintentional, I love how the three Bengali books are different from one another. For a light weekend read, there’s The Moving Shadow, for a heavier, historical novel, there’s Tiger Woman and The Aunt who wouldn’t Die is best for any day.

A ghost who asks about a young wife’s sex life and curses her unapologetically; the formation of the first Bengali circus and story of the first Indian woman who performed with tigers; and desi pulp fiction. How thrilling! Here are three book recommendations, all translated from the Bengali by the prolific, Arunava Sinha, who has done more than 44 translations so far. Though unintentional, I love how the three Bengali books are different from one another. For a light weekend read, there’s The Moving Shadow, for a heavier, historical novel, there’s Tiger Woman and The Aunt who wouldn’t Die is best for any day.

THE AUNT WHO WOULDN’T DIE BY SHIRSHENDU MUKHOPADHYAY, TRANSLATED FROM THE BENGALI BY ARUNAVA SINHA

Three women, the widowed aunt (Pishima) named Roshomoyee, the new bride, Somlatha, and the fiesty, confused, Boshon (Somlatha’s daughter), have their lives entangled with one another in Shirshenu Mukhopadhyay’s Goynar Baksho, translated by Arunava Sinha. Soon after Somlatha’s marriage into a supposedly wealthy family, the aunt, who entrusts her box of precious jewels in secret, dies under mysterious circumstances. But she comes back as a nagging, bitter ghost to haunt Somlatha.

Pishima chants ‘Die die die’ unapologetically. She is a seasoned prankster, sprinkling sugar on mattresses, messing up the salt levels in the food cooked by Somlatha and often prodding the young wife for details of her sex life. Married at seven and widowed at twelve, Pishima has experienced neither happiness nor pleasure in life, thus ending up as a bitter, ghost. There is a scene where Pishima asks Somlatha to season fish with paanchphoron, a pinch of sugar and baking soda, tempting her to savour it as she isn’t a widow. This reminded me of Mayukh Sen’s essay in Food52 ‘The Sad, Sexist, Past of Bengali Cuisine’. I don’t know for sure if the essay and the book talk of the same time period and caste, but I’d recommend it for further insight on how certain groups of Bengali widows were treated in the 1900s. In the story, Pishima is allowed only one meal a day, forced to fast and has to abstain from meat.

Probably as a sadistic move by the ghost of Pishima, Somlatha finds clumps of hair and lizards in her meat and fish. But at other times, Pishima transforms into a kindred spirit. She urges Somlatha to own her sexuality with ‘eat him up eat him up’, warns her about the men in the family calling them ‘bastards, swines’, and exposes their secret love lives with their mistresses . At best, Pishima and Somlatha are the modern day ‘frenemies’.

The novel presents the story of an East Bengali zamindari family in the decline. Men don’t work but live off their dwindling wealth and take lovers. The jewellery box is symbolic of the power and agency that widowed women, like Pishima, could exert in a patriarchal household that imposes cultural restrictions on them. Somlatha, the ‘ideal Indian wife’ in the story, manages the household, lays the groundwork for a sari business to help the family out of their debts, and weans off husbands from lovers; yet she needs someone like old Pishima to remind her not to forget herself. Boshon was quite under developed in the story and fails to evoke a similar fondness as one feels for Pishima and Somlatha.

Nevertheless, The Aunt who wouldn’t Die is a rapid read, deftly introducing us to the three main women in the narrative and trotting off to sudden twists in plot and muffled giggles.

Rating : 4.5/5

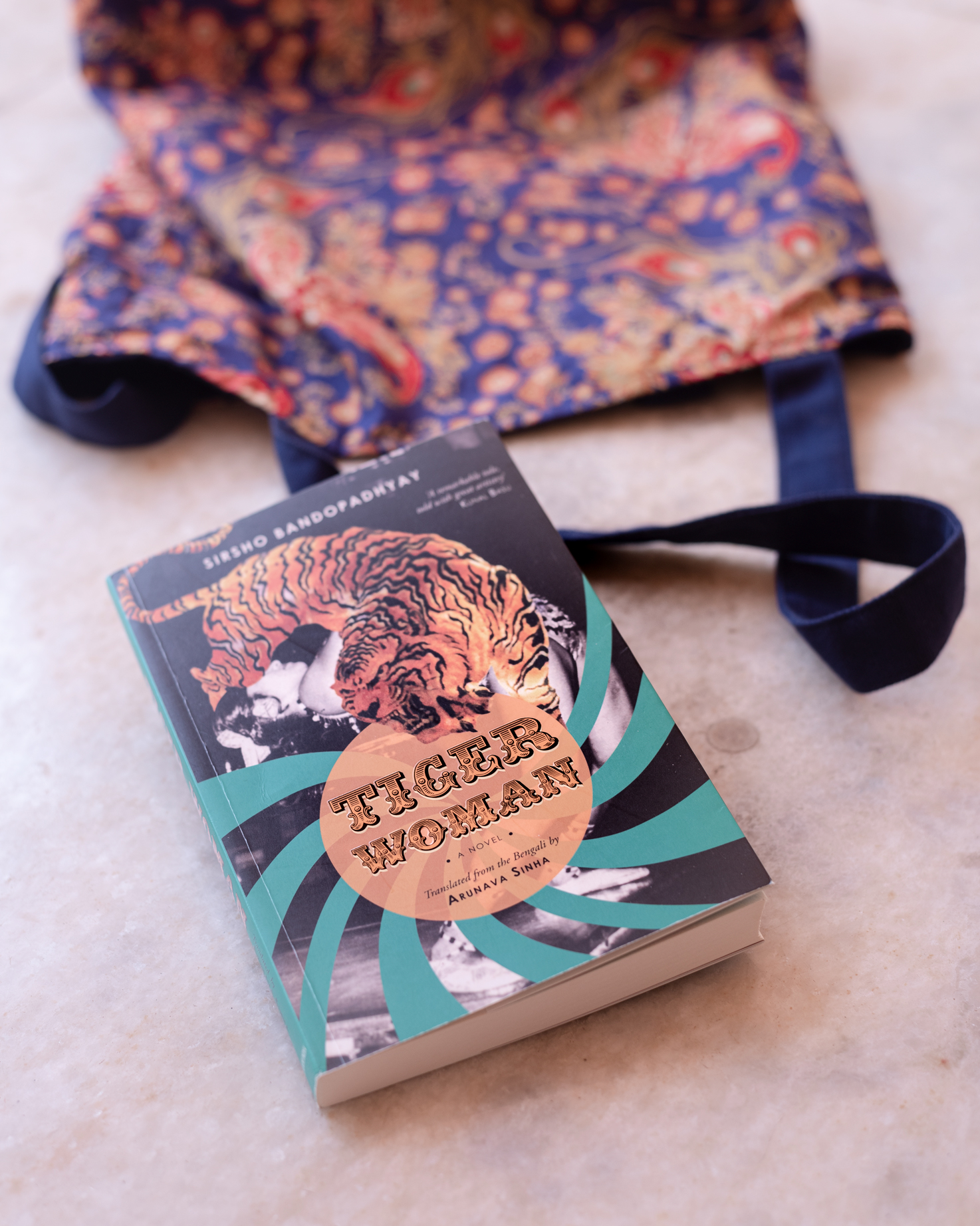

TIGER WOMAN BY SIRSHO BANDOPADHYAY; TRANSLATED FROM THE BENGALI BY ARUNAVA SINHA

1904, Calcutta Maidan — When the circus ended, a man walked onto the stage. Close behind him was a tusked elephant bearing an intricately patterned throne on which sat a tiger and a lady in a white sari with a red border and a crown on her head, holding a flag that read ‘Bande Mataram’. It was the flag of independent India. The man, Priyanath, shouted ‘Bande Mataram’. The audience chorused back the same. Tiger Woman, the English translation of the Bengali novel, Shardulsundori, encapsulates this fervour of nationalistic identity. Set over the landscape of Calcutta, Rajasthan, Agarthala and Singapore, it follows a man, Priyanath Bose, who dreams of establishing the first Bengali circus when the field is majorly under the control of Americans and Europeans. This is an era when a circus is stamped as a ‘disgrace’ and ‘nationalwallah’, a name for those who preach for freedom from the British, is a taunt.

Reading Tiger Woman was an arduous task. I finished it over many nights, and in short bursts at the doctor’s waiting room and in cafes. I didn’t love it at first, but it grew on me, especially after I read the Author’s note at the end which pushed me into a googling blackhole. Priyanath is a real person! And so are the characters in the novel (also references to real life figures such as sister Niveditha and Swami Vivekananda). I was hooked.

The titular, ‘tiger woman’ or Suhasini appears only towards the middle of the book, after which the sluggish pace drastically changes into a wondrous gallop. Though not an easy read, the novel has an eclectic cast — Ganpathi, mind-reader, ganja-addict Brahmin and magician who has a secret stash of ‘a buffalo head complete with horns, human skulls and bones’, rival circus owners, Bador who sleeps with his tigers, and Suhasini, the first Indian woman to perform with tigers in a circus. There is a divide in the social sentiments of different age groups in contrast to present day — Priyanath wanted to start a circus at the age of 17, his family had started looking for a bride for him when he was 19, sex was not limiting (the forced sex by Ganpathi at the age of 14 with a distant relative, after her bath, was quite disturbing though), and a man named Badrudozza who wishes to be called Bador is renamed Badalchand as his other name is too ‘difficult’.

Tiger Woman — A historical novel about the rise of nationalism in the 1800s and the formation of the first Bengali circus. Based on real life, we follow the man who dreamed of circuses and the woman who performed with tigers Share on X

There was competition between other circuses in the country. When Seasons Circus displayed a ‘woman in a suit and a hat, with a whip in her hand’ with a tiger, Priyanath knew he had to introduce new acts. Later he expands his business by purchasing the ‘Great Indian Circus’ which made ‘Great Bengal Circus’ get trained animals (forty horses!) and artistes. The book is blurbed with the circus being a metaphor for the rise of nationalism in the country, and gives a glimpse of nearly fifty years of Indian history (1872-1920). Though unevenly paced with a fidgety narration that often loses track, Tiger Woman proves to be an important historical novel.

Rating : 3/5

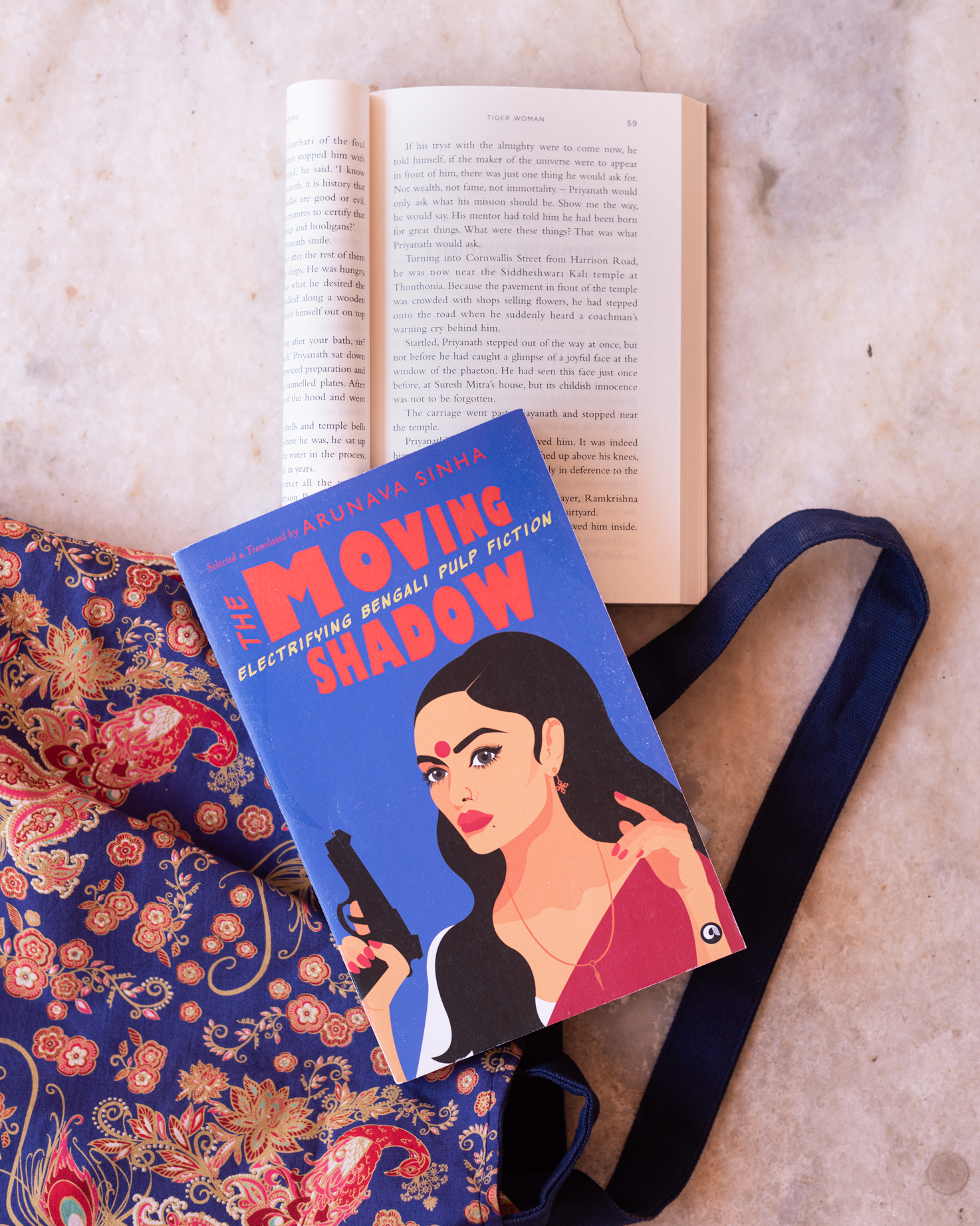

THE MOVING SHADOW : ELECTRIFYING BENGALI PULP FICTION; TRANSLATED BY ARUNAVA SINHA

Often, books, especially from non-whites, are burdened with the task of conveying a moral, or following a conventional arc of redemption. But this anthology of translated stories from mainstream and pulp writers from India and Bangladesh, including Satyajit Ray, Swapan Kumar and Muhammed Zafar Iqbal, comes as a breath of fresh air. There are no morals, no enlightenment; just bliss, chuckles and gasps. And ample clichés. The stories are sensational, scandalous, often predictable but nevertheless entertaining. Starring ‘an intelligent femme fatale, scientists as spies, womanizers, a ventriloquist whose dummy starts greying and a robot who falls in love’ — this book was one of my picks for the ‘Best Summer Reads of 2019 on Huffpost India’.

The Moving Shadow is a collection of eight short stories and novellas. Four stories are grouped under ‘Crime’ and form the bulk of the book and the other four are shorter reads filed under the ‘Horror’ section. The Bengali noir was indulgent, at times tiresome because of a stretched out plot line. Iqbal’s story, Copotronic Love, was interesting and features a robot falling in love, a much explored story idea but executed well. I loved the quest in solving the mystery of the Bidri bowl led by an Indian-Sherlock Holmes in Parashar Barma Makes a Bid by Premendra Mitra. It was slow, reminiscent of middle brow crime fiction, tempting to follow along.

Bengali noir and horror stories — Scandalous, sensational stories aka desi pulp fiction for your guilty pleasure. Read for an Indian Sherlock Holmes, spies, femme fatales, dummies who come to life, ghosts, black magicians and more. Share on X

The horror stories were my sugar rush. Each one was different from the one before it, short enough to pack a punch that makes you go ‘Ah’ at the end. Satyajit Roy’s Bhuto has a dummy of a ventriloquist gone rogue and maintains a spooky, eerie atmosphere of suspense. I also loved the patient-doctor dynamics in Saradindu and This Body by Gobindolal Bandyopadhyay which was one hell of a twisted tale. Read this indulgent desi pulp fiction anthology for stories that entertain.

Rating : 4/5

A bitter, sadistic ghost who becomes 'frenemies' with her niece-in-law; desi pulp fiction; a historical novel about circus and nationalism in the 1880s. These books translated from the Bengali are a treat. Share on XDisclaimer : Much thanks to Bee Books for a copy of The Aunt who wouldn’t die and Pan Macmillan for a copy of Tiger Woman. All opinions are my own.

YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

Two Indian SFF about witches, assassins and puppet shows — Ambiguity Machines and Magical Women

Meena Arora’s compendium of popular folktales and myths from India — The Blue Lotus